|

Senator Russell and Col Hathaway in Azerbaijan

all color photos courtesy Robert Gros |

The Sighting

A slightly run down passenger train rattled slowly down the shore of the Caspian Sea in the warm autumn sunlight. In its last car, a dingy wooden carriage studded with tin stovepipes, four American tourists peered through streaky windows. Since leaving Baku they had hardly noticed the natural beauty of the passing Azerbaijani scenery; instead, their attention was drawn to a trainload of landing craft on the adjacent track, and the oil wells, guard towers and clusters of soldiers that punctuated the marshy coast. Intourist -- the KGB-run Soviet state travel agency -- had fouled up. The train had departed almost two hours later than scheduled, and the Americans were restless. Three of them, Army Lieutenant Colonel Edward N. Hathaway, Reuben Efron, an attorney from Washington, DC and Robert Gros, a California businessman, were chatting in one of the compartments. The fourth member of the group, Senator Richard Brevard Russell, had a cold, and was resting in his bunk next door.

In the spring of 1955, the Georgia Democrat had decided to embark on an extended tour of American military facilities in Europe, a type of "fact-finding" mission he had used profitably in the past to generate leverage for bigger defense budgets. When Russell and Hathaway sailed for Europe on the SS United States on August 18, he told reporters that he wanted to see firsthand "if we are getting the defense we should for the money." He downplayed rumors that he would cap his European trip with an excursion through the USSR, even though his office had applied for his Soviet visa long before.

As chairman of the powerful Armed Services Committee and one the Senate's senior members, Russell was one of the most influential men in Congress. The former Governor of Georgia, perennial presidential candidate, and conservative (some would say reactionary) pro-segregation Senator was a most dedicated Cold Warrior. And in an era when there was no formal Congressional oversight of the intelligence community, Russell was the Central Intelligence Agency's chief ally in the Senate. Defense contractors looked to Russell as a friend too. Lockheed's Georgia division, for example, employed thousands of his constituents. In April, the first production C-130 Hercules transport, destined to become one of the company's most enduring successes, had taken to the air at Marietta. In the secret realm, Lockheed-Georgia was a major contractor for the Air Force's Aircraft Nuclear Propulsion (ANP) program aimed at developing a nuclear-powered bomber with theoretically unlimited range. Russell was a strong supporter of ANP, and Lockheed was planning to build a special reactor in Georgia to conduct experiments with nuclear-powered aircraft systems.

Russell was disappointed that his friend and protege Lyndon Johnson and Johnson's wife Lady Bird were not accompanying him, as Russell had originally arranged. It is difficult to picture Johnson, the ambitious, workaholic Senate majority leader, taking two months off to join Russell on his European junket; in any case, Johnson's near-fatal heart attack on July 2nd had forced him to drop all plans.

Russell's itinerary was packed with visits to US and NATO military bases. He made stops in London, Madrid, and Paris. In early September he flew to Germany for excursions to airfields at Wiesbaden (soon to host U-2 operations) and Kaiserslautern, then moved on to Frankfurt, Amsterdam, Copenhagen, Oslo, and Helsinki. In Finland he and Hathaway would meet up with Reuben Efron, a Russian-born US citizen who would accompany Russell as his translator during his two week stay in the Soviet Union. The CIA had a long-standing program to garner intelligence from Western travelers in the USSR. Efron kept detailed notes on the trip and distilled them into a long journal full of comments on Soviet food, living quarters and economic conditions. Colonel Hathaway, a member of the Congressional military liaison staff, was tasked with observing items of defense interest. The men clearly took their roles as amateur spies seriously, meticulously noting details of items that were probably of slight interest to intelligence analysts.

Russell, Hathaway and Efron arrived in Leningrad on September 23, and then took a train to Moscow three days later. In the capital they made the usual tourist rounds. Russell nettled his Soviet hosts by insisting on taking a car the seventy miles to Borodino, the site of Napoleon's 1812 defeat of the Russian army. On the way to the monument, Hathaway dutifully noted that exactly forty-two kilometers west of Moscow there was an installation sporting an obsolete copy of an old World War II German radar set. In Moscow, Russell crossed paths with another American who happened to be in the middle of a long visit to the USSR: Robert R. Gros, a San Francisco utility executive.

See: Robert Gros

|

Russell with Soviet Intourist guides |

After spending a few days in Stalingrad the Americans flew to the famous oil city of Baku, the capital of the Soviet republic of Azerbaijan, where they were placed in the care of the latest in a succession of Intourist guides, a squat woman with steel teeth whom Russell promptly nicknamed "Snappin' Annie." "Annie" took them to the approved tourist sites in the town, but the party decided that they wanted a better overview of the Caspian Sea and pressured her to take them to the Stalin monument on a hill overlooking the city.

|

Efron, Russell, Soviet guides, Col Hathaway at war memorial overlooking Baku click to enlarge |

The Senator and Col Hathaway each carried 35mm cameras, and Gros had a 16mm movie camera in addition to his Leica, which was loaded with Kodak color film. For the benefit of analysts back home, and over "Snappin' Annie's" protests, the tourist spies clicked away at what they were sure were items of immense strategic interest along the waterfront. Gros thought he could see submarines, which seems odd considering that the Caspian Sea is landlocked.

|

Soviet train on Baku-Tbilisi line |

On the evening of October 4, 1955 they made their way to the crowded Baku railroad station. When they finally settled into their train carriage, Efron noticed that a tall, stocky military officer, apparently a one-star General, occupied one of the other compartments. The doors at the ends of the cars were locked, so the travelers would be effectively isolated until their arrival in Tbilisi, Georgia, the next morning. They finally got underway around six o'clock. The rail line ran southwest along the Caspian and made a sharp dogleg to the west-northwest near the town of Alyat, Alayatskaya or Alat on some maps (and which the group later referred to in its reports as "Atjaty"). At this point, the train was less than seventy-five miles from the Iranian border. It stopped briefly at the Alyat station at about seven o'clock.

|

|

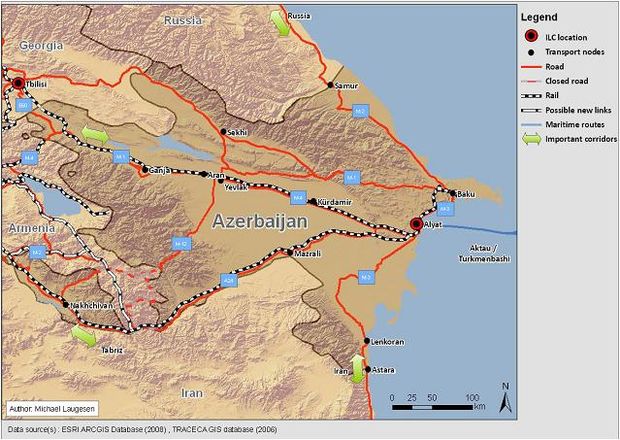

Approximate location of sighting was a few miles southwest of Alyatskaya (aka. Alat, Alyat), which is about 40 miles south from Baku, Azerbaijan. The Alyatskaya train station's location is 39.9768° N/49.4076° E and about 2.5 miles north of Alyatskaya, Azerbaijan. Iran is about 70 miles south to the closest point on the Iranian border. Train lines are the white and black dash lines. The Russell group took the northern train route to Tbilisi, Georgia. |

The Senator, who was feeling a bit ill, was resting on his bunk in his darkened sleeper compartment and watching the passing scenery as the train pulled out of station and resumed its leisurely progress toward the Caucasus mountains and Soviet Georgia. About ten minutes out of the station he noticed a small light that seemed at first to be a reflection in the window. He realized in a moment that it was in the sky outside, some distance from the train. It resolved into a spinning, glowing, yellow-green dot, which rose rapidly into the air on a nearly vertical path.

Russell burst into the compartment next door and shouted "I just saw a flying saucer!" Someone switched off the lights and all four men crowded to the window in time to catch a glimpse of the dot disappearing high and to their right. It was moving fast. Gros went to his compartment, grabbed his cameras and began filming. A few moments later, all four men saw a second light flare up a mile or two to the south and spiral up into the darkening sky. It followed much the same path as the first. To Hathaway and Efron, it seemed to be circular, about the size of a fighter plane, spinning rather slowly, and emitting a hint of fire or sparks. There was no smoke trail, and any sounds it might have made did not carry over the noise of the train. As Gros remembers it, the object's motion was rapid: "it shhhhot into the sky!" There were one or two searchlights shining toward the train from near the takeoff point, leading the men to assume that the site was a military base, despite their inability to see any runways or structures. Night was rapidly falling; nothing more was visible. The train rolled on, and the Americans stayed glued to their windows, straining to see more. Soon the conductors came through and pulled the blinds, gesturing that further sightseeing was forbidden. The dumbfounded Americans rolled helplessly into the night.

|

Train stopped in Caucasus mountains, probably the morning following the sighting |

|

Russell and Efron with guides, possibly in Sochi a few days after the sighting |