|

Tremulis

at Wright Field, illustrating B-29, circa 1942

|

Archetypal Engineering

Alex Tremulis: Saucer Designer

Like many Americans, Alex Sarantos Tremulis had been intrigued by the press coverage of flying saucers in the summer of 1947, and he was not convinced that they were just optical illusions. In January 1948 an Air Force pilot had died chasing one. Tremulis was different from most people who read the Mantell story in two respects: he was one of the most talented automobile designers in the United States, and he had worked at Wright Field during WWII as an aircraft technical illustrator.

Tremulis had started his career in 1936, when at the tender age of 22 he was hired to replace Gordon Buehrig as chief stylist of the legendary Auburn-Cord-Duesenberg firm. He was responsible for several beautiful Auburn designs, sleek cars like the Model 812 "Boattail" with its supercharged Lycoming engine and bulging chrome exhaust pipes.

|

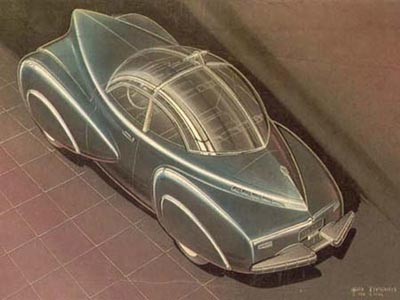

Advanced Cord concept by Tremulis, 1936 |

Shortly after the US entered World War II in 1941, Tremulis was drafted. He had always loved airplanes, so he took a chance and sent a portfolio of imaginative designs to the Army Air Force. The paintings worked their way up to the desk of General "Hap" Arnold, the Chief of Staff, who must have been greatly impressed. Alex was soon transferred to Design Branch of the Aircraft Laboratory at Wright field, the Air Force's most advanced development center, where the aeronautical technology of the future was being forged.

Master Sergeant Tremulis won over his initially skeptical military superiors with his ability to transform sterile blueprints into beautiful, action-packed renderings. It dawned on them that these drawings could help them sell planes in Washington. General Oliver Echols, the Air Corps deputy Chief of Staff, was so pleased with Tremulis's work that he asked him to illustrate all future proposals from the Aircraft Lab. For his part, Tremulis was somewhat awed by the technology of Wright Field, and was impressed by visits from VIPs like the legendary aerodynamicist and Air Force consultant Theodore von Kármán. Tremulis obviously enjoyed painting one 1943 concept, a sleek, flame-spewing jet helicopter piloted by a gent in a double-breasted business suit, but he eventually moved on to more serious designs, including a supersonic fighter built around four new, secret GE TG-180 turbojet engines and an April 1944 concept for a supersonic research rocket plane that might be the first drawing of what eventually became the Bell X-1.

|

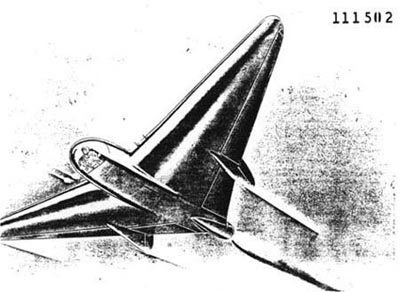

Forward-swept wing rocket-fighter concept with pilot in prone position similar to Northrop MX-334, about 1944 |

|

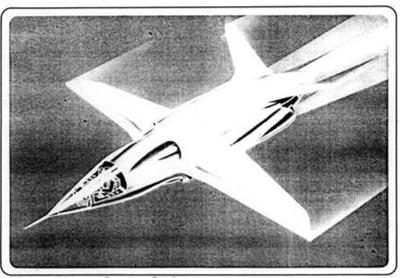

"The Lady In Red," a 1944 concept for a supersonic jet with four engines |

|

Tremulis rendering of rocket-powered supersonic research aircraft, forerunner of the X-1 |

A post-war history of the Aircraft Lab recounted the impact of one of his more exotic ideas:

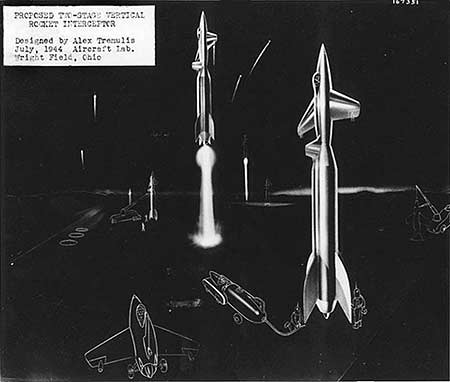

Once [Tremulis] let his imagination run wild and drew a radical design that stood on a three-wheeled carriage and was launched by firing rockets; it shot straight up to fabulous heights and then used its own power to fight with. The story goes that it was pooh-poohed into the wastebasket by a high-ranking colonel, who never did call up Al after he found out in Germany that the Nazis had a similar design in the fabrication stages. The plane the Germans had, incidentally, was to be used to bomb New York. Stupid thinking here had stopped it from even being considered.

The New York bomber could have been either the Sanger "Rabo" or Peenemunde's A9/10, and the shortsighted Colonel might have been Donald Putt.

Tremulis called his rocket plane, which he sketched in July 1944, the "TVT," for "Tremulis Vertical Takeoff." It looked like an Me-163 mounted on the tip of a V-2. In good Buck Rogers style, he depicted one of the machines sitting on its launch pad and being fuelled by a pair of space-suited technicians wearing bubble helmets topped with antennas.

|

"TVT" vertical takeoff rocket interceptor, based on German concepts. Note space-suited technicians refueling craft

click to enlarge |

Eventually Tremulis was given a Top Secret clearance and access to information about the strange new weapons being introduced by the Germans. One day in 1944 he had an encounter with the shadowy world of Air Technical Intelligence when he was taken under tight security to a restricted room at Wright Field. Inside was a pile of mangled wreckage. "This is a German V-2 rocket," he was told. "We want you to draw a picture of what it looks like when it's in one piece."

The Tucker '48

When the war ended, Tremulis left the Air Force and returned to the tamer world of civilian industrial design. Near the end of 1946 a magazine article about an intriguing new automobile caught his interest. It was a futuristic, airplane-like machine called the "Tucker Torpedo." He contacted the car's creator immediately. Preston Tucker, a charismatic industrialist, was maneuvering for a toehold in the expected postwar-boom car market and was busily organizing investors and a national sales network. Tucker and Tremulis were impressed with each other, and soon Tremulis joined the firm as chief designer, restyling Tucker's impractical concept car and overseeing every detail of the creation of a genuine running prototype.

|

Original Tucker rendering by Tremulis |

|

Tremulis, right, supervising construction of Tucker clay buck |

|

Tucker '48 prototype, June 1947: a spaceship for the road |

When the Tucker '48 rolled out on June 19, 1947, five days before Kenneth Arnold's "flying saucer" sighting that would launch the modern UFO era, it was largely Tremulis's design, and it was like nothing else on the road. "The first completely new car in fifty years," said the ads.

But by late summer 1947 there already were signs of trouble with Tucker's company. The Securities and Exchange Commission began questioning Tucker's business practices, and other government agencies blocked his attempts to purchase surplus industrial property for factory space. In June 1948, the SEC would launch formal a formal investigation of the company, a persecution that would ultimately lead to its demise the following year. Tucker and several company officials would be charged with multiple counts of fraud, and Tremulis would eventually be forced to take the witness stand to defend his prototyping techniques.

Imagineering the Saucer

Tremulis may have needed a diversion from the rollercoaster Tucker enterprise as he read the papers on January 8, 1948. Something about the Mantell crash riveted him. He was already intensely interested in flying saucers, he was steeped in the futuristic jet and rocket culture of the Wright Field Aircraft Lab, and he was one of the best-qualified men in the world to illustrate exotic machines in a believable way. Were flying saucers spaceships from other planets? If so, how would they work? What would the pilots look like?

|

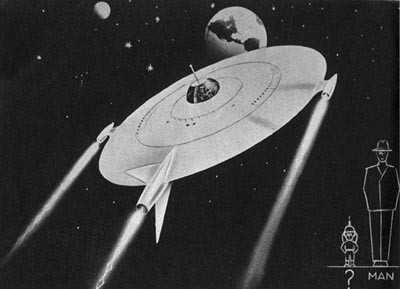

click to enlarge |

His saucer streaked through space against a black, starry background. It was heading straight for Earth, where North America was prominently visible. It sported three big rocket engine pods spewing flames complete with realistic supersonic shock diamonds. There were air intake louvers and little hatches on top of the wing for verisimilitude, and in the center of the disc was a cockpit bubble topped with an antenna. Inside the bubble, at the controls of the saucer, were two little, bald extraterrestrial pilots in space suits. In the lower right corner of the painting, Tremulis drew an outline of a human figure, "MAN," an average guy in a business suit. Next to "MAN" was a dwarfish creature wearing a Buck Rogers helmet with an antenna, something like the one in his Wright Field "TVT" drawing. The little creature was labeled "?"

He took the rendering to the Chicago Tribune. The drawing and Tremulis's credentials impressed the editors. "I could build a scale model of this thing that would fly," he told reporters, and wowed them with an accurate estimate that an interplanetary spacecraft would have to be able to reach 25,000 mph to escape Earth's gravity. The drawing was distributed nationally by the Acme wire service.

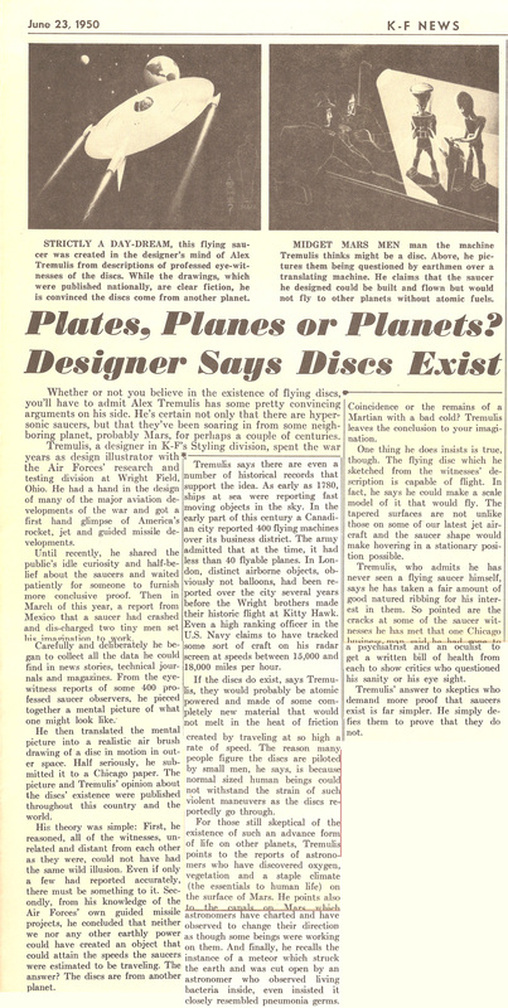

In October, 1949, Variety columnist Frank Scully reported that a saucer had crashed in New Mexico and that the government had recovered the bodies of its dwarfish crew. Scully published a book, Behind the Flying Saucers, in 1950, and Donald Keyhoe's article "The Flying Saucers Are Real" in the January edition of True magazine raised public interest in saucers to new heights.

Tremulis quickly produced another rendering even more unusual than the first. It was a portrayal of two humans conducting a classic "third degree"-style interrogation of a pair of small, bulb-headed extraterrestrial beings. One of the humans appears to be an Air Force officer (General Vandenberg, perhaps?) who is holding a microphone linked to a sleek machine from which a tape emerges. The tape is being examined by one of the extraterrestrials, who is wearing a helmet topped with a coiled antenna. The concept behind the drawing appears to be that the "translation machine" transmits voice communication from the human interrogator to the ET via the helmet, and that the "brain waves" of the ET are in turn passed to the machine for transcription into human language. A cigarette-smoking man reads the tape as the ET passes it along. Is he a CIA official?

The facial features of the ETs are extremely intriguing. To modern eyes, they look exactly like the "standard Grey alien" described in recent abduction literature, with their large heads and wraparound eyes. Their boot-belt-and-tunic outfits are dated and science-fiction-clichéd, but the overall impression is rather arresting.

|

click to enlarge |

By March, 1950, when public interest in saucers was peaking, both of Tremulis's illustrations were in wide circulation in newspapers.

|

Sources

Many of the above illustrations were graciously provided by Tremulis' wife Chrisanthie, who also recalled her late husband's considerable interest in the flying saucer phenomenon.

Anecdotes of Tremulis's career at Wright Field from They Tamed The Sky: The Triumph of American Aviation, by Douglas J. Ingells (New York City: D. Appleton-Century Company, 1946) and the article "Tuckers, Gyros and Little Green Men," in Exotic Cars Quarterly, Fall 1992. Tremulis is also portrayed in Francis Ford Coppola's film Tucker: The Man and His Dream.

Tucker information and links can be found at www.tuckerclub.org