|

|

|

Paper Threat

The first intercontinental weapon system: Japanese Fu-Go balloons

At about

quarter past six on the evening of December 6, 1944, three men and a woman

working outside a coal mine near the town of Thermopolis, Wyoming, heard

a soft whistling sound overhead. There was an explosion. They looked up

and saw flames high in the sky, and something like a parachute floating

down. The next morning, searchers found a small crater nearby.

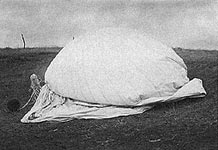

Less than a week later, two men stumbled on the crumpled remains of what

seemed to be a large balloon strewn in a forest near Kalispell, Montana.

They reported the incident to local authorities, who in turn notified

the FBI. Inspection of the debris revealed Japanese markings. The Army,

Air Force and Navy were informed of the discovery.

On December 31, another deflated balloon was found tangled in a tree near

Etascada, Oregon. Charred metallic equipment dangled from it. Investigators

carefully dislodged the pieces and carted them to the local high school,

where they spread the fragments out on the floor of a tennis court for

study. From the looks of it, the device might have been hanging in the

tree for three or four days.

More strange

debris turned up in Alaska and Saskatchewan. A few papers ran a story

about the bomb-dropping balloon in Wyoming, but the other incidents received

little publicity. Suddenly, on January 4, official wartime censorship

clamped down. Pending further notice, editors were instructed to withhold

all printed or broadcast news about the balloons.

Initial US Confusion and Concern

It was a

most unlikely turn of events. The U.S. government was shocked that so

late in the war it would suddenly have to confront the renewed prospect

of air attack against the American mainland. Though the public remained

largely unaware, the military had some warning that something might be

going on. In the preceding weeks, pieces of large balloons had been fished

out of the ocean near Hawaii and off the coast of California. The initial

report of the bomb near Thermopolis and sporadic retrievals of shredded

balloon debris of unknown origin in the following days increased concerns,

but the magnitude and exact nature of the threat was still unclear. Sightings

of balloons in flight soon began coming in to air defense facilities;

the first air interception of an unidentified balloon was fruitlessly

attempted on December 19 over Los Angeles.

Technical

Intelligence teams quickly organized an intensive study of the recovered

mystery balloon components. What they found was startling. Despite initial

speculation that the devices might be coming from Japanese detention centers

in the Pacific Northwest, analysis of the equipment carried by the balloons

led to the conclusion that they were probably originating in Japan itself.

Using common materials, simple components, and sophisticated weather forecasting,

the Japanese had evidently developed the first operational intercontinental

weapon delivery system.

The first

concern of US authorities, once the origin of the devices had been established,

was the exact nature of what they could carry. In the second week of December,

Colonel Murray Sanders, a bacteriologist from Fort Detrick, Maryland,

the Army's biological warfare center, flew to Washington state to examine

the collected debris.

The balloons were brought in, and we all stood around them, in a circle [Sanders recalled]. All the scientific and military experts, all of us with our own thoughts. We examined them, and then we went away to make our own individual reports. Mine scared them stiff....I told them that if we found Japanese B-encephalitis on any of the balloons we were in real trouble. Mosquitos were the best vectors - and we had plenty of those in the States - and our population had no defenses against B-encephalitis....four out of five people who contracted it would have died, in my view.

Sanders was concerned about other possibilities:

Anthrax is a tough bug.... [the Japanese had] used it in China. They could have splattered the west and southwest of Canada and the United States.They could have contaminated the pastures and forests and killed all the cows, sheep, horses, pigs, deer -- plus a considerable number of human beings. The hysteria would have been terrible; one of the strengths of [biological warfare] as a weapon is that you can't see it, but it kills.

The menace

of balloon-delivered toxicological materials was taken seriously. In at

least a few instances, civilians were startled to see recovery personnel

dressed in full protective garments prodding balloon wreckage with long

poles, searching for evidence of germ-dispensers or chemical agents. As

the debris was carted off for analysis, witnesses were told to keep quiet

about what they had seen.

Canadian

authorities provided Sanders with a mysterious little plastic box that

they had found in balloon wreckage in Saskatchewan. To his relief, there

were no dangerous microorganisms in it (it was probably nothing more sinister

that the celluloid container protecting the balloon's battery). Sanders

commandeered an old B-19 bomber and started a personal aerial reconnaissance

of the Pacific Northwest, searching for downed balloons.

To forestall possible outbreaks of disease, under a program called "Lightning Project," the Army's Western Defense Command quietly began to stockpile decontamination supplies in areas deemed at greatest risk. Farmers' organizations and veterinarians were advised by government agencies, without elaboration, to be particularly watchful for unusual diseases in crops or livestock.

Technical Details and Intelligence Analysis

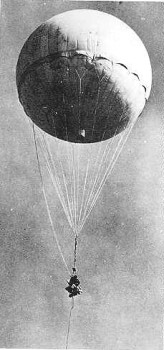

The Japanese

called the balloon weapons Fu-Go ("Fu" being the first character

of the Japanese word for balloon). They were assembled by hand -- usually

by schoolgirls after classes -- and made from cheap, non-critical materials.

The balloons themselves were thirty-three feet in diameter, made of a

type of paper derived from a common Japanese shrub, and gas-proofed with

vegetable starch. Suspended by cables from the spherical balloon envelope

was an aluminum ring, about three feet across, which supported a control

and ballast system and the bomb load. Around the rim of the ring was a

series of 32 "blow-out plugs" similar to explosive bolts. Each

plug supported a ballast sandbag.

The balloons

were launched, partially filled with hydrogen, from several sites on the

east coast of Honshu, the Japanese main island. Climbing rapidly, they

would soon reach a cruising altitude of about 30,000 feet. Japanese Army

researchers had discovered that at these heights there existed high-speed

currents of wind which could carry the Fu-Go all the way to North America.

Above 16,000 feet, the hydrogen would expand the envelope into a spherical

shape. As night fell and the gas cooled, the balloons would begin to shrivel

and lose altitude. At a predetermined minimum altitude, barometric switches

would snap closed, energizing electrical circuits to the blowout plugs.

A pair of ballast bags would be cut free, and the Fu-Go, lightened, would

begin to climb back into the high-altitude windstream. If the balloon

flew too high, a spring-loaded valve would release a puff of hydrogen.

Day and night the cycle repeated. If all went according to plan, by the

time the last plugs, fastened to the bombs, were fired, the balloon would

be over enemy territory. As a final step, a flash-bomb attached to the

balloon was supposed to detonate, incinerating the evidence and adding

to the mystery of the device's origin. The plans were ambitious. 10,000

of the inexpensive Fu-Go were going to rain bombs on North America. In

November, 700 were actually launched; the next month, 1,200.

At first, American authorities were not greatly concerned by the small

fire-bombs carried by the balloons, but they realized that if biological

warfare agents turned out to be present on the balloons, it would be necessary

to mount a full-scale interception effort. In preparation, they needed

to thoroughly understand the balloon's design and flight performance.

Several well-preserved examples were quickly reassembled and tested by

military labs. Elaborate blueprints of all components were prepared. The

ballast system was analyzed to determine cruising altitude and endurance.

The US military was concerned that the radars it possessed would have

trouble detecting the balloons at their high float altitudes; by the middle

of February, several Fu-Go were sent to Army radar laboratories in New

Jersey for reflectivity tests. Samples

of sand from recovered ballast bags were distributed to geologists for

analysis. Based on the analysis of fossil marine microorganisms in one

sample, the scientists made a remarkably accurate guess at its launch

site. Ballast from another balloon found in Canada contained distinctive

particles of blast furnace slag, giving another clue to its origin.

Fu-Go and the US Fire Raids

The initiation

of the Japanese balloon bombing campaign against the US came just as the

American strategic bombing of Japan was moving into its decisive phase.

The huge new Boeing B-29 Superfortress was operating in increasing

numbers against the Japanese home islands from bases in China and the

Marianas Islands. In the preceding months, the bombers had dropped their

loads of high-explosive bombs from high altitudes, aiming by radar to

avoid flak and fighter interception with inevitable reduction of strike

accuracy. On November 24, 1944, the first US strike on Tokyo since the

famous 1942 Doolittle raid produced little significant damage.

In the fall

of 1944, a panel of experts under the direction of Dr. Vannevar Bush had

noted the that unique nature of Japanese targets -- largely densely packed

wood and paper structures -- could make incendiary bombing much more effective

than the so-called "precision bombing" techniques in standard

use. Special clustered fire bombs were developed for the B-29s, and experimental

raids in late December had favorable results. By the beginning of the

new year, General "Hap" Arnold, Chief of Staff of the Army Air

Force, had assigned generals Curtis LeMay and Roger Ramey the task of

leading bombing operations against Japan. On January 3, 1945, in a major

escalation of the fire-bombing technique, fifty-seven B-29s, each carrying

about three thousand pounds of incendiaries, struck Nagoya.

At 5:40 on

the evening of January 4, a small incendiary bomb fell from the sky and

exploded on a farm outside Medford, Oregon. About a half hour later, a

largely intact Japanese balloon settled into a field near Sebastopol,

California, bearing four fire bombs. It was these incidents, combined

with concerns over biological warfare, which provoked the imposition of

censorship about the Japanese balloon attacks. The American public was

not to know that the Japanese were striking back in kind (if not in proportion).

For the next

two months, Fu-Go arrived over North America in increasing numbers. 2,500

of the devices drifted through the North Pacific skies in February alone,

and despite the obstacles of distance, weather, and mechanical malfunction,

many survived to reach the US and Canada. Bombs fell in California and

Saskatchewan. Fu-Go debris was discovered in Arizona, Alaska, Iowa and

Nebraska. A few balloons were intercepted and shot down by fighters. Soon

reports were coming in at the rate of several per day. Bits of metal,

fragments of paper, exploded and unexploded bombs turned up in Washington,

British Columbia, Manitoba, Idaho, Colorado, Michigan, Mexico, Texas.

One Fu-Go even dropped in Everett, Washington, uncomfortably close to

the Boeing plant.

By the end of March, American intelligence authorities produced an "estimate",

or probability study, of the possible purpose of the Japanese balloon

campaign. In descending order of probability, they concluded that the

devices were employed for:

1. Bacteriological

or chemical warfare, or both.

2. Transportation of incendiary and antipersonnel bombs.

3. Experiments for unknown purposes.

4. Psychological efforts to inspire terror and diversion of forces.

5. Transportation of agents.

6. Anti-aircraft devices.

The vital

Boeing facilities near Seattle had to be guarded at all costs. As the

Everett balloon had shown, sheer coincidence could bring a bomb down in

some critical spot. Even a brief disruption of B-29 production had to

be avoided. Civilian morale was a fragile thing. If the Japanese learned

that their attacks were having an effect, they would be encouraged to

increase the tempo of launches. In the worst-case scenario of the actual

use of biological warfare substances in the balloons, large portions of

the Pacific Northwest might be in grave danger. The threat of balloon-ignited

forest fires was an additional nightmare. If the incendiary bomb flights

continued into the dry summer months, a major disaster was all too possible.

Nearly three thousand soldiers were put on call to fight balloon-ignited

fires.

Prior to the advent of the Fu-Go, the Army had largely dedicated its west coast air bases to training activities due to the lack of a realistic air threat from Japan. It quickly began to construct a suitable network of command and control facilities to deal with the balloon problem. To protect the strategic installations surrounding Seattle, the Army initiated "Sunset Project," an integrated radar warning and fighter control system.

Sunset Project

The

Project's early-warning radar network west of Seattle consisted of three

search radars, with two more sited southwest of the city and another based

at Paine Field. In addition, a contingent of hundreds of civilian spotters,

called the Ground Observer Corps, was trained to scan the skies for strange

objects. (it is unclear whether the GOC observers were told the exact

nature and importance of the targets they were seeking. In view of the

secrecy surrounding the Fu-Go it seems possible that full details were

withheld).

Contacts

by GOC observers and search radars would be relayed to a Filter Center,

where air defense officers would consolidate sighting reports with information

about weather conditions, known air traffic and the status and location

of interceptor aircraft. If an observation was judged to be a genuine

hostile target, the Filter Center would scramble an interceptor. The fighter,

usually a Lockheed P-38 Lightning or Northrop P-61 Black Widow,

would be directed to the vicinity of the target by another type of radar

facility called Ground-Controlled Intercept (GCI). GCI controllers would

track both the unknown target and the interceptor, guiding the fighter

to the vicinity of the unknown where its on-board radar should be able

to acquire the target. In view of the nature of the targets, an easy kill

could be expected. The system was partially in place by late April 1945.

On February 19, Curtis LeMay elevated the firebombing of Japan the top

priority of his command. Six days later, 450 tons of incendiaries rained

on Tokyo. LeMay made an even bigger shift in tactics a few days later,

when he ordered his crews to strip their bombers of nearly all defensive

armament and make their next drops from a mere 6,000 feet. Late on the

windy night of March 9, B-29s began to incinerate downtown Tokyo. 279

of the huge bombers unloaded 2,000 tons of napalm into the crowded homes

and factories of the capital. An incredible hurricane of flame erupted

from the paper city. Sixteen square miles were obliterated, 100,000 were

killed; 1,000,000 were left homeless.

On the afternoon

of March 10th, a soggy Fu-Go sank from a rainy Washington sky and floated

into the high-tension power lines leading from the Bonneville Dam. The

lines shorted and protective gear shut them down. Power was lost to a

portion of the state. Inside the blacked-out region was the Manhattan

Project's supersecret Hanford Works, where the new "B" Reactor

was generating plutonium for experiments at Los Alamos, the headquarters

of America's top secret nuclear bomb project. Deprived of its electric

cooling pumps, "B" Reactor shut down. It was three days before

full production could be resumed.

Ironically, the Tokyo fire raid helped to bring an end to the Fu-Go project.

Subcontractors were destroyed and hydrogen production was disrupted. US

censorship had denied the Japanese significant intelligence on the effectiveness

of the weapon. Continued effort seemed wasted. Launches virtually ended

in April.

By the time

the elaborate Sunset Project balloon interception network became fully

operational in May, there was no longer a Fu-Go threat to counter. The

setup and integration of the radar stations had taken almost two months,

but the highly motivated and primed observers were finally equipped and

ready to scan the skies. At several bases, interceptors stood alert to

engage and destroy the deadly intruders, and antiaircraft artillery sites

were on hair-trigger status.

The watchers

expected balloons, and even though there were no more Fu-Go, they saw

them: sixty-eight times interceptors were scrambled by the Seattle Control

Group on non-existent Fu-Gos which turned out, on further investigation,

to be Navy blimps, Venus, or the weather balloons launched four times

a day from the bigger airports in the country.

The interceptor force commanders were puzzled by the continual false alarms. There was obviously some fundamental problem with visual tracking of unknown aerial objects. Both ground personnel and fighter crews would benefit from practical experience with locating and intercepting realistic targets under controlled circumstances. The idea of repairing captured Fu-Go and sending them toward Seattle was mooted, and there was even a proposal to develop special target balloons for training purposes. The schemes were never implemented and the Sunset Project died with the end of the War.

But the Fu-Go saga was not over. Over 9,000 had been launched. The grounded remains of hundreds of the lethal devices were scattered over a vast area of North America -- pieces would continue to turn up into the 1960s -- and the public was largely unaware of their existence. On May 5, 1945, two adults and five children were picnicking in a forest near the small town of Bly, in south central Oregon, when they stumbled on the ballast device of a downed Fu-Go. One of them must have tampered with it. A fragmentation bomb still attached to the device exploded, instantly killing one of the adults and all five children. Incredibly, secrecy remained in place for another two weeks. Finally, on May 22, over a month after Fu-Go launches had probably ended, the US government issued a statement warning of the Japanese balloons and the hazards of handling strange debris.

The Japanese finally had scored a propaganda victory, and they proceeded to exploit it. Broadcasting in English on June 4, a Japanese military spokesman claimed that the launches up to that point had merely been experiments. Soon, "large-scale attacks with death-defying Japanese manning the balloons" would be launched. It was a seeming confirmation of the worst-case US estimate in March. US technical intelligence engineers quickly calculated that a manned balloon using Fu-Go technology was feasible. The diameter of the envelope would have to be doubled, and a pressurized gondola would be necessary to insure the survival of the occupant at stratospheric altitudes for the four days needed to cross the Pacific. If launched from a ship or submarine close to US coastal waters, however, such a device might be less complex. [1]

Shortly after the June 4 statement, another Japanese spokesman threatened ominously that the Fu-Go were merely a "prelude to something big."

J. Robert Oppenheimer, the director of the Manhattan Project, would recall an incident at Los Alamos, high on a remote plateau in New Mexico, just before the fateful Trinity nuclear tests test on July 16, 1945:

Very shortly before the test of the first atomic bomb...I remember one morning when almost the whole project was out of doors staring at a bright object in the sky through glasses, binoculars, and whatever else they could find; and nearby Kirtland Field reported to us that they had no interceptors which had enabled them to come within range of the object. Our director of personnel was a man of some human wisdom; and he finally came to my office and asked whether we would stop trying to shoot down Venus.

The most brilliant physicists in the world were no less prone to war jitters than anyone else. Some of the scientists were convinced that they could see a "gondola" hanging from the "balloon."

Fu-Go and the 1947 Connection

There are several aspects of the Fu-Go story that helped pave the way for the "Flying Disc" flap of 1947.

The Fu-Go devices were unique in many fundamental respects - they were intercontinental-range weapons of unprecedented and remarkably original design; they were provided with means of self-destructing by burning; they were fragile and lightweight; and they scattered themselves randomly over North America. The Japanese balloons were the object of recovery operations by both military intelligence organizations and the FBI. When the initial Disc reports came in in 1947, some of these parallels were noted, and some of the same personnel who had been involved in the early 1945 recoveries again participated in investigation of reported crashes of the new objects.

The unique ballast control devices on the balloons, the real breakthrough that made their trans-Pacific range possible, were studied by US balloon designers in the postwar period and helped provide the inspiration for more advanced systems that would be applied to US high-altitude "constant-level" balloon projects. These eventually culminated in the altitude control devices installed on the famous "Skyhook" balloons that were responsible for so many UFO sightings in the late 1940s and early 1950s.

But perhaps the most significant long-term effect of the Fu-Go affair was that it established a precedent for official secrecy and censorship surrounding reports of recoveries of suspected airborne artifacts of foreign origin - at least in wartime.

|

FBI Special Agent W G Banister examines Fu-Go that fell in Kalispell, Montana on December 11, 1944. Army Air Force Maj J E Bolgiano studies balloon's pressure relief valve as Army Intelligence Capt W Boyce Stanard looks on [2]

|

|

The 1947 "Disc crash" reports followed a similar pattern, as in this hoax case investigated by Banister [Tacoma News-Tribune, 12 July 47]: FBI Drums Up Cymbals-Like 'Disk' in Idaho BUTTE, Mont, July 11 - AP - FBI Agent W. G. Banister said an object which appeared to be a "flying disk" was found early today at Twin Falls, Ida., and turned over to federal authorities there. Banister, special agent in charge of the FBI in Montana and Idaho, said the bureau had reported the discovery to the army at Fort Douglas, Utah. An FBI agent in Twin Falls inspected the "saucer" and described it as similar to the "cymbals used by a drummer in a band, placed face to face." The object measured 30 1/2 inches in diameter, with a metal dome on one side and a plastic dome about 14 inches high on the opposite side... |

Meteor expert Dr Lincoln LaPaz was another individual who would become involved both in the Fu-Go affair and later UFO events.

LaPaz headed the mathematics and meteoritics departments at the University of New Mexico in addition to consulting with the military on the Proximity Fuze project, which conducted tests against simulated Japanese aircraft on a range near Kirtland Army Air Force Base. Parallel with this wartime military work, LaPaz continued to manage a meteor-observation network in the US that used observers in widely-separated locations. In early 1945 LaPaz's observers began to report sightings of many unusual "point meteors" which seemed to flare up and disappear without moving. Soon after the first Fu-Go debris was recovered LaPaz realized what the "point meteors" had really been - the self-destruct charges burning up the balloons after they dropped their deadly payloads.

In postwar press releases, the University of New Mexico described how LaPaz then began to utilize his meteor network as a dedicated Fu-Go observation and reporting system. These documents provide the segue between LaPaz's study of the Japanese bombing balloons and his investigation of postwar meteor events in terms of possible enemy activity.

In late 1948, when another wave of unusual light phenomena began to be reported in the southwestern US, LaPaz would begin to collect and evaluate reports.

See: Green Fireball Chronology

Sources and Notes

[1] As bizarre as the idea of waves of attack balloons occupied by suicidal Japanese soldiers may have seemed, the threat had some substance. The Japanese had proven all too willing to resort to suicide attacks. They had designed two different types of aircraft -- one propeller-driven, one rocket-powered -- specifically for use by Kamikaze suicide pilots. The rocket-boosted machine, the MXY-7 Ohka (Cherry Blossom), was actually used in combat in the final stages of the war, as many as 75 being launched at Allied targets in the vicinity of Okinawa. A Kamikaze balloon would be an unlikely but not totally impossible extension of this technique. When the Kalispell, Montana Fu-Go was recovered in late 1944 and before the imposition of censorship, Newsweek magazine openly speculated (1 Jan 45 issue) that the balloon might have been used to transport an agent from Japan. Moreover, the Japanese had developed a special version of the Fu-Go that was intended to be launched from submarines - but carried only a new form of special incendiary payload designed to burn forests.

[2] For the record, this is the same W Guy Banister who became a figure in the JFK assassination mythos in the 1960s. No endorsement of these conspiracy theories is intended or implied. However, years after his involvement with the Fu-Go and Twin Falls "disc" incidents, Banister made bizarre and intriguing statements linking unusual outbreaks of cattle and crop diseases in the US and Canada to "airborne germs" that he believed originated in Russia. Could this be a clue that he had the same ideas about the 1947 saucers?

Mikesh, Robert C., Japan's World War II Balloon Bomb Attacks on North America (Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1973)

Rhodes, Richard, The Making of the Atomic Bomb (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1986)

Webber, Bert, Silent Siege III: Japanese Attacks on North America in World War II (Medford, OR: Webb Research Group Publishers, 1997)

Williams, Peter and David Wallace, Unit 731: Japan's Secret Biological Warfare in World War II (New York: The Free Press, 1989)