|

Strike From Space?

Orbital Bombs, UFOs and The Great Northeast Blackout of 1965

[Draft 24

Mar 02]

In

the fall of 1965, conservative activists Phyllis Schlafly and Rear Admiral

Chester Ward (Ret) published a remarkable, if now largely forgotten book

called "Strike From Space," aimed at warning America about the

growing menace of exotic Soviet space weaponry. "Strike From Space"

was clearly the product of behind-the-scenes work by members of the Goldwater

wing of the Republican party – or perhaps even more conservative

circles – and bitterly attacked the military policies of the Lyndon

Johnson administration. Schlafly and Ward reserved particular venom for

Defense Secretary Robert Strange McNamara (they loved to use his middle

name), whom they regarded as a representative of an elite social clique

that was bent on deliberately undermining US security in the face of a

growing Soviet nuclear threat.

In

the fall of 1965, conservative activists Phyllis Schlafly and Rear Admiral

Chester Ward (Ret) published a remarkable, if now largely forgotten book

called "Strike From Space," aimed at warning America about the

growing menace of exotic Soviet space weaponry. "Strike From Space"

was clearly the product of behind-the-scenes work by members of the Goldwater

wing of the Republican party – or perhaps even more conservative

circles – and bitterly attacked the military policies of the Lyndon

Johnson administration. Schlafly and Ward reserved particular venom for

Defense Secretary Robert Strange McNamara (they loved to use his middle

name), whom they regarded as a representative of an elite social clique

that was bent on deliberately undermining US security in the face of a

growing Soviet nuclear threat.

Schlafly and Ward relied on a star-studded cast of military advisors when researching the book, probably including generals like Curtis LeMay and Thomas Power, both former chiefs of Strategic Air Command. According to Schlafly, another strong supporter and friend was Hoover Institution strategic theorist Dr Stefan Possony, who had long been an advocate of strengthened space defenses. Possony and his assistant Gen George Keegan (in the 1970s, Assistant Chief of Staff, Air Force Intelligence) had been members of the ultra-hawkish Air Force Intelligence Special Studies Group in the 1950s. (And Possony had been an attendee at the 1953 CIA UFO Scientific Advisory Panel meetings). Possony’s and Keegan’s deep, almost paranoid distrust of Soviet motives and their approach to analysis of Soviet space developments is vividly described in books like Kaplan’s "The Wizards of Armageddon."

Of course, the early 1960s was an era of very impressive Soviet space advances. Every week seemed to bring news of a new space probe, a record-setting satellite payload, or a huge new missile. As Johnson and McNamara’s cancellation of systems like Dyna Soar and the B-70 bomber enraged the conservatives, Schlafly, Ward and their advisors were determined to expose what they saw as a carefully-planned slide toward an inevitable Soviet first strike – a nuclear Pearl Harbor that would use a new type of weapon – not ICBMs, but orbital bombs that could strike from the heavens without warning, from any direction, in an unstoppable, massive decapitating blow. McNamara was deliberately ignoring this possibility, the ultraconservatives argued, and America needed to wake up.

Here is how

Schlafly and Ward portrayed the coming Soviet sneak attack:

|

Have the Soviets the capability of launching a crippling strike from space on the United States? In March 1965 General Curtis LeMay, recently retired as Air Force Chief of Staff, warned that Russia might be developing space weapons that would give them military superiority over the United States. Also in March, Air Force General Thomas S. Power, for 7 years head of the US Strategic Air Command, warned that Americans 'may wake up one morning' and find a number of nuclear-armed Soviet satellites 'floating in stationary orbits over every part of the United States.' On July 4, 1965, Communist Party Chief Brezhnev, in a Kremlin speech, declared that the Soviets possess 'orbital rockets.' Two weeks later the Soviets launched the heaviest space craft payload ever orbited. Named Proton 1, it weighed 26,500 pounds - more than 10,000 pounds heavier than the previous Soviet satellite. Only one day earlier, the Soviets had orbited 5 unmanned satellites with a single rocket. On September 3 they launched 5 more the same way. In the light of these actual demonstrations of massive rocket- thrust capability, plus the fact that they have has 4 years to multiply the 100-megaton warhead capability they demonstrated by tests in October 1961, and to improve their yield/weight ratio, no responsible authority can deny the possibility that the Soviets possess 'gigaton' warheads, orbital bombs, and multiple warheads for super-missiles.This would mean that the Soviets have the capability to accomplish their world conquest by strategic nuclear weapons. First, their attack against the United States could be delivered with complete surprise -- with 'zero warning' - because an orbital bomber carrying a warhead in the gigaton range does not need to be deorbited before the button is pushed. Second, the attack could destroy or render inoperative up to 90% of US strategic retaliatory forces. Our so-called 'invulnerable' land-based missiles are not designed to withstand such unprecedented explosive power, and all our remaining bombers (except the few on airborne alert) are vulnerable with less than 15 minutes warning; nor could our communications, command and control networks function after such an attack. Third, the attack would be "genocidal," that is, the entire population of the United States would be the prime target. This genocidal result could be re-insured 30 minutes later by a follow-on attack with multiple-warhead missiles, ideal for annihilating entire population centers, and still later by their manned bombers which, unlike missiles, can seek out undestroyed areas. ...Stacked in space, stockpiled in the sky - the Soviets now have more than 85 known Cosmos satellites, with unknown payloads. How many of the Cosmos are orbital bombers, armed as General Power warned they could be, with 'multi-megaton nuclear weapons which could be released upon radio command from Russia"? No one from our side knows the answer. We do have a clue - from high authority on their side: from First Party Secretary Leonid Brezhnev, former czar of the Soviet space program, co-conspirator in the plot to destroy the United States from Cuba. In mid-summer 1965, published boasts in US papers of McNamara's small-warheaded US missiles had put the US number at 800 and had downgraded Soviet multi-megaton missiles to 200-300. The Kremlin felt it could afford a little derisive understatement in reply: "We hate to boast, and we do not want to threaten anyone," Brezhnev confided delicately to the graduates of the Soviet Military Academies in Moscow. "However, it is necessary to note that the figures and calculations quoted in the West about rocket and nuclear power of the Soviet Union do no credit at all to the intelligence services of imperialist states." Pentagon war planners are constantly writing up 'scenarios' for 'war games' so they can play-act-out versions of future wars. What would a scenario of a strike from space be like? At evening rush hour on the east coast, 3 gigaton orbital bombs would be fired by radio command with zero warning - each covering 1/3 of our nation. The Proton 1 fleet would be de-orbited and exploded over major population centers and Minuteman missile areas. All communication and command facilities would be hopelessly damaged, including our 'Looking Glass' Command on continuous airborne alert. Even if there were any US officials left alive with authority and the code to command our Polaris submarines to retaliate, how could he communicate? The attack would continue immediately with missiles from Soviet submarines, from Cuba, and over the South Pole. Within 15 minutes, the Cosmos series of orbital bombs would be de-orbited and fired, plus 100-megaton missiles fired from Siberia. Soviet bombers would arrive soon after to mop up any targets still undestroyed. Secretary McNamara estimated 149 megadeaths from a Soviet missile attack - and he did not figure space weapons or bomber mop-up. The stark fact is - if the Soviets play this scenario for real - the American people would then be assassinated as a whole. The Soviets would then hold the rest of the world in ruthless slavery.

|

Schlafly and Ward’s book was published in November 1965. And what is most remarkable about it is that – as will be seen shortly – its lurid sneak-attack scenario immediately seemed to come true.

Orbital Nuclear Bombs

The concept of Soviet orbital bombs had been broached early on in the space age – as early as 1947, in fact, when an FBI agent reported a scientist-informant’s rumor of a secret search for "atom bombs in the stratosphere" by Fred Whipple's Harvard Meteor Project using the Baker Super Schmidt Meteor Camera built by the Perkin Elmer corporation for meteor photography. Of course, orbital bombs were virtually fantasy in 1947, but by the early 1960s the possibility that the Soviets would develop such systems was under serious consideration in the US. According to Soviet space history expert Asif Siddiqi, high-level deliberations about orbital weapons began in the USSR as early as 1959, and by 1962, three of the major Soviet rocket design bureaus were well into development of prototype systems.

These spacecraft are known technically as "Fractional Orbital Bombardment Systems," or FOBS – "fractional" referring to the fact that the missile places the nuclear payload in orbit, but after completing only a fraction of a revolution of the planet, the warhead fires a retrorocket that brings it down on the intended target. Likewise, the warhead may remain in orbit as a Multiple Orbital Bombardment System, or MOBS.

The strategic advantage of such a weapon stemmed from the fact that ordinary ICBM warheads rise hundreds of miles into space on their ballistic trajectories and can be detected by long-range warning radars long before they reach their targets. In the early 1960s, NORAD Ballistic Missile Early Warning System radars were aimed at the North Polar region, where Soviet land-based ICBM raids were expected to appear. A FOBS warhead, placed in a low-altitude orbit over the South Pole, or approaching the US from virtually any other azimuth, would not be detected by US radars until the last moments before impact. Defense would be nearly impossible. FOBS missiles were therefore considered to be first-strike, sneak-attack systems intended to blind and decapitate an adversary before followup raids by more conventional systems.

In the context of the massive Soviet missile buildup of the early 1960s it’s not hard to understand why senior US military officers were concerned with such developments, since they potentially undermined the whole basis of the US deterrent system. The typically more cautious CIA did comment on FOBS as well, according to Siddiqi:

[CIA analysts concluded that] the Soviets have the capability to develop an orbital bombardment satellite and might decide to launch and deorbit a space weapon at an early date for propaganda or political reasons.

There was a strong implication that such weapons would only be effective as propaganda weapons and be seen as militarily ineffective by the Soviets because of their poor accuracy compared with conventional ICBMs. In mid-1963, the CIA prepared a dedicated report on Soviet orbital bombs which did not deviate significantly from the findings of the earlier pronouncement:

We have thus far acquired no evidence that the USSR plans to orbit a nuclear-armed satellite in the near term, or that a program to establish an orbital bombardment capability is at present seriously contemplated by the Soviet leadership. However the USSR does have the capability of orbiting one or possibly a few nuclear-armed satellites at any time, and at comparatively small cost. [1]

Of the three competing Soviet FOBS concepts, the Yangel R-36 (State designation 8K69, NATO designation SS-9 Scarp) was selected for development in April 1962. Construction was started on new launch facilities for the missile in January 1965, and this must have been noted by US reconnaissance experts. By the spring of 1965 US officers were publicly referring to Soviet orbital missiles, as Schlafly noted in her book.

|

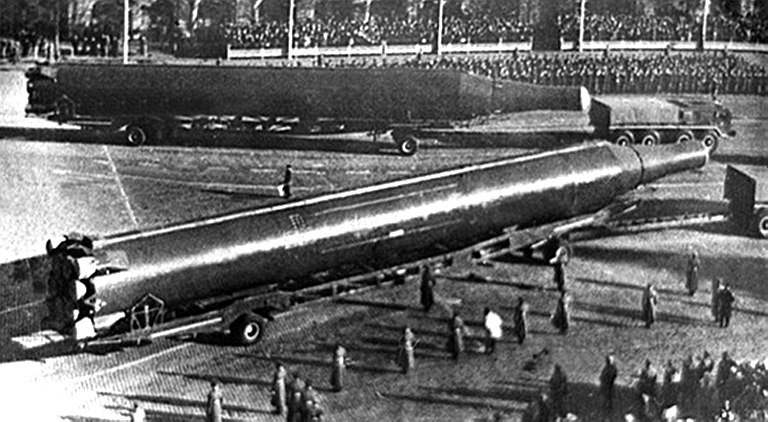

Yangel R-36 (NATO SS-9 Scarp) experimental Fractional Orbital Bombardment System launcher |

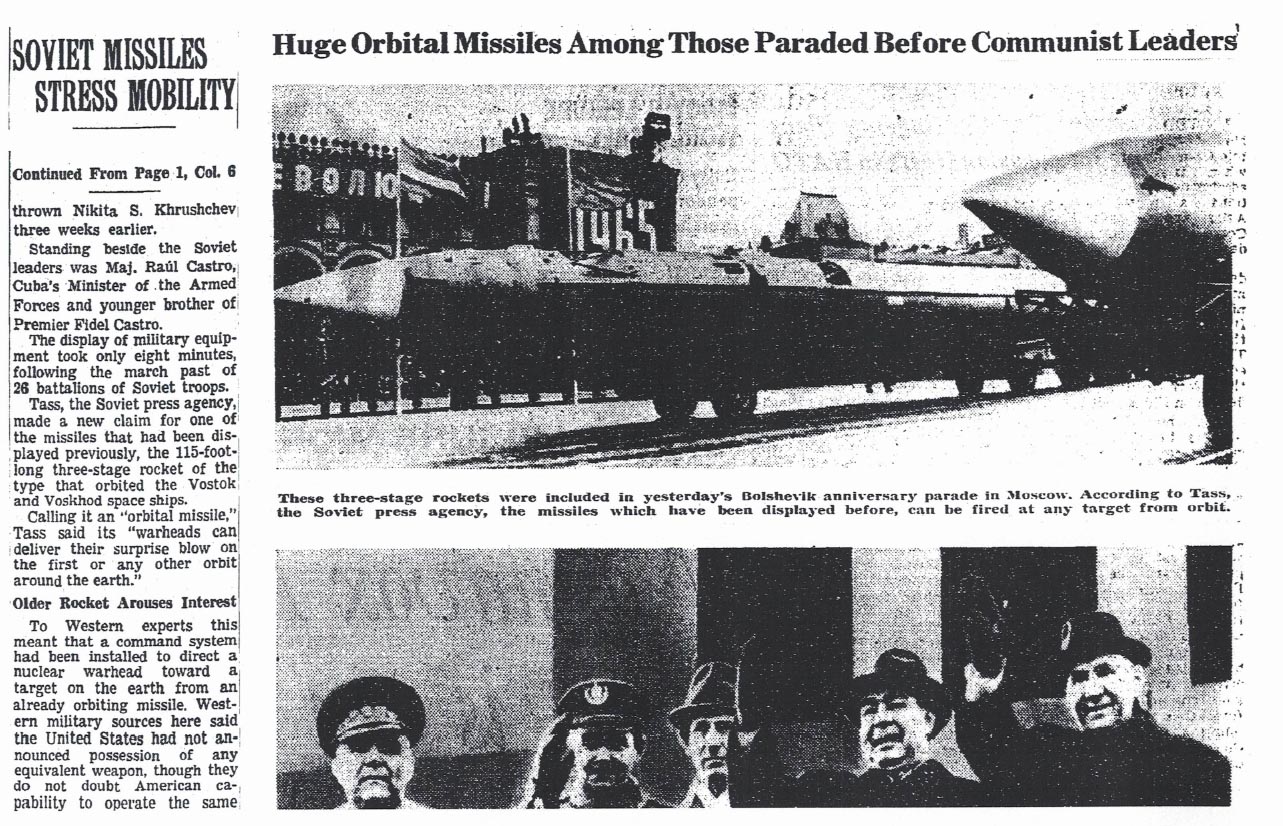

But FOBS weapons hit the front pages of US newspapers in early November 1965, when they suddenly appeared in a major display in Moscow. On Monday, November 8, the New York Times ran banner headlines on the previous day’s military parade marking the anniversary of the Bolshevik Revolution: "New Soviet Missiles Rumble Through Moscow…Huge Orbital Missiles Among Those Paraded Before Communist Leaders." The missiles capped what was actually a comparatively restrained display that began with 26 battalions of troops marching through Red Square past reviewing stands where the Soviet leadership, including Party Secretary Brezhnev, Defense Minister Rodion Malinovsky, and Fidel Castro’s brother Raul looked on.

|

The Soviet heirarchy views the "huge orbital missiles" during November 7 Red Square parade |

"The display of military equipment took only eight minutes," the Times reported.

Tass, the Soviet press agency, made a new claim for one of the missiles that had been displayed previously, the 115-foot long three-stage rocket of the type that orbited the Vostok and Voskhod ships. Calling it an "orbital missile," Tass said its "warheads can deliver their surprise blow on the first or any other orbit around the earth." To Western experts this meant that a command system had been installed to direct a nuclear warhead toward a target on the earth from an already orbiting missile. Western military sources here said the United States had not announced possession of any equivalent weapon. [2]

The announcement of the FOBS capability of the missile seems to have taken some US circles by surprise, and on November 9, the Times noted that

the State Department said today that it was studying whether the Soviet Union had violated a United Nations disarmament resolution with its asserted development of an "orbital missile." There was concern that this signaled a Soviet retreat from one of the few arms agreements that have been reached between the United States and the Soviet Union – an agreement to prevent the arms race from spreading to space weapons…. The department’s reaction was described by officials as more than just a psychological riposte to what may have been primarily a propaganda claim by the Soviet Union. According to Robert J. McCloskey, the department’s spokesman, the question of a possible violation was being studied seriously at "fairly high levels throughout the government."

The State Department may have been "concerned," but it seems probable that military leaders were much more worried by the Soviet announcement.

Strike From Space?

Just a few hours after the Times article describing US concern about the new Soviet orbital bombs hit newsstands, at 5:16 on the evening of November 9th, a massive cascade of power surges shot through the electrical transmission grid of the Northeastern United States. Circuit after circuit overloaded and tripped offline, and within moments, power ceased flowing to almost everyone living and working within a region encompassing some 80,000 square miles of New York State and New England as well as the Canadian shore of Lake Erie … nearly 30 million people. New York City and a dozen other major population centers dropped into frightening pitch darkness and rush-hour confusion. [3]

Meanwhile, in an underground command post called High Point, near Berryville, Virginia, Air Force Colonel J Leo Bourassa was gazing into the abyss. Bourassa was in charge of an Office of Emergency Preparedness (OEP, an ancestor of FEMA) installation that was intended to be the Presidential Bunker in event of a nuclear attack. High Point, or Mt Weather, was linked to a national network of nuclear blast detection devices called System 210-A, or "Bomb Alarm." [see Western Union Technical Review of the Bomb Alarm Display System 210-A]

Designed

to react only to the distinctive optical double flash of a nuclear explosion

and transmit signals by telegraph landlines to displays in locations like

High Point, Bomb Alarm was a primary indicator of nuclear events in the

days before satellite NUDET sensors. The Bomb Alarm display board at High

Point was blazing with yellow lights, indicating that communications links

to the BMEWS site in Thule, Greenland, as well as twenty-one other System

210-A sites, had gone down. But worse – much worse – two of

the sensors, the ones for Salt Lake City and Charlotte, North Carolina,

were showing red. Red for nuclear detonations. Bourassa assumed the worst

– that a surgical nuclear attack was under way – and placed

Mt Weather on full alert. It was the one and only time that the facility

went on alert during the Cold War. [4]

Designed

to react only to the distinctive optical double flash of a nuclear explosion

and transmit signals by telegraph landlines to displays in locations like

High Point, Bomb Alarm was a primary indicator of nuclear events in the

days before satellite NUDET sensors. The Bomb Alarm display board at High

Point was blazing with yellow lights, indicating that communications links

to the BMEWS site in Thule, Greenland, as well as twenty-one other System

210-A sites, had gone down. But worse – much worse – two of

the sensors, the ones for Salt Lake City and Charlotte, North Carolina,

were showing red. Red for nuclear detonations. Bourassa assumed the worst

– that a surgical nuclear attack was under way – and placed

Mt Weather on full alert. It was the one and only time that the facility

went on alert during the Cold War. [4]

While I have seen no documentation specifically linking the Northeast Blackout Alert to the Kremlin’s FOBS display two days before, it seems likely that OEP officers in charge of "Continuity of Government" installations like High Point would have received daily briefings on new military developments such as the Tass declaration about orbital warheads. And the fact is that the indications Bourassa saw on his boards may have played out a scenario that may have been increasingly on the minds of military planners looking for signs of a Soviet sneak attack, because it probably looked much like the effects of electromagnetic pulse (EMP) from high-altitude nuclear bursts.

High-altitude EMP effects had been confirmed by the rocket-launched 1958 Argus shots in the South Atlantic and Hardtack tests in the Pacific, and more recently by the Starfish series of exoatmospheric thermonuclear blasts that tested a prototype Air Force antisatellite missile system. Power had been knocked out in Hawaii by some of the tests, and by 1965 the new Minuteman ICBM force was being actively hardened against EMP damage. It would have been very easy for Bourassa to assume that the massive blackout in the Northeast, coupled with indications of surface bursts in other locations, was the opening round of a Soviet surprise attack. If Bourassa had just heard the Soviet boasts about their new FOBS missiles, his decision to declare the alert is even more understandable.

There seems to be no indication that other US military forces increased their alert status because of the power failures, but the story might have been different if Washington or other major command centers had been inside the blackout zone.

One of the more fascinating aspects of the Blackout is the timing of the prescient Schlafly/Ward book and the Soviet revelation of its FOBS missiles. Schlafly had predicted that the Soviet first strike would occur without warning at evening rush hour on the East Coast and would use orbital weapons. It seems odd, given the level of technical jargon achieved by the book, that it contains no discussion of EMP effects, particularly since Schlafly was eager to emphasize other devastating effects of Soviet high-yield bombs (which she speculated would reach the "gigaton" range in the near future). I recently emailed Schlafly to ask whether she knew of EMP at the time, and if so, why it was not mentioned in the book. In a brief message she stated that she and Ward did know about the phenomenon, but gave no explanation for its omission.

Electromagnetic Effects

A "great event" like the Northeast Blackout of 1965 reverberates on many social planes. Bourassa’s Bomb Alarm alert was one kind of reaction. Another revolved around UFOs.

UFO reports cascaded in from the blacked-out region, and some of them were spectacular, particularly the ones centering on a critical electrical substation in Clay, New York, near Syracuse, where large glowing orbs were sighted by several witnesses. (It seems hard to avoid the thought that the widespread, paralyzing blackout resonated with memories of the similar events depicted in the 1951 UFO film "The Day The Earth Stood Still.") UFOs became as inextricably tied to the 1965 event as the legend that a mini baby-boom took place nine months later. [5]

On July 29, 1968, Dr. James E. McDonald, one the most intelligent, knowledgeable and capable scientists to ever tackle the UFO phenomenon, testified before the House Committee on Science & Astronautics (which happened to include a young Illinois Representative named Donald Rumsfeld at the time) in the wake of the unpopular University of Colorado UFO study (or Condon Report). The report had noted the spate of UFO reports during the Blackout and had devoted several pages to discussion of power outages related to UFO incidents. McDonald was interested in the concept of electromagnetic effects associated with UFOs and was asked to comment on this by Representative William F. Ryan, a Democrat from New York City:

Mr. Ryan: Let me ask a further question: In the course of your investigation and your study of UFO sightings, have you found any cases where contemporaneously with the sighting of UFO's allegedly, there were any other events which took place, which might or might not be related to the UFO's?

Dr. McDonald: Yes. Certainly there are many physical effects. For instance, in Mr. Pettis' district, several people found the fillings in their mouth hurting while this object was nearby, but there are many cases probably on record of car ignition failure. One famous case was at Levelland, Tex., in 1957. Ten vehicles were stopped within a short area, all independently in a 2-hour period, near Levelland, Tex. There was no lightning or thunder storm, and only a trace of rain.

There is another which I don't know whether to bring to the committee's attention or not. The evidence is not as conclusive as the car stopping phenomenon, but there are too many instances for me to ignore. UFO's have often been seen hovering near power facilities. There are a small number but still a little too many to seem pure fortuitous chance, of system outages, coincident with the UFO sighting. One of the cases was Tamaroa, Ill. Another was a case in Shelbyville, Ky., early last year.

Even the famous one, the New York blackout (Nov 9 1965), involved UFO sightings. Dr. Hynek probably would be the most appropriate man to describe the Manhattan sighting, since he interviewed several witnesses involved. I interviewed a woman in Seacliff, N.Y. She saw a disk hovering and going up and down. And then shooting away from New York just after the power failure. I went to the FPC [Federal Power Commission] for data, they didn't take them seriously although they had many dozens of sighting reports for that famous evening. There were reports all over New England in the midst of that blackout, and five witnesses near Syracuse, N.Y., saw a glowing object ascending within about a minute of the blackout. First they thought it was a dump burning right at the moment the lights went out. It is rather puzzling that the pulse of current that tripped the relay at the Ontario Hydro Commission plant has never been identified, but initially the tentative suspicion was centered on the Clay Substation of the Niagara Mohawk network right there in the Syracuse area, where unidentified aerial phenomenon has been seen by some of the witnesses.

This extends down to the limit of single houses losing their power when a UFO is near. The hypothesis in the case of car stopping is that there might be high magnetic fields, d.c. fields, which saturate the [ignition system solenoid] core and thus prevent the pulses going through the system to the other side. Just how a UFO could trigger an outage on a large power network is however not yet clear. But this is a disturbing series of coincidences that I think warrant much more attention than they have so far received.

Mr. Ryan: As far as you know, has any agency investigated the New York blackout in relation to UFO?

Dr. McDonald: None at all. when I spoke to the FPC people, I was dissatisfied with the amount of information I could gain. I am saying there is a puzzling and slightly disturbing coincidence here. I'm not going on record as saying, yes, these are clear-cut cause and effect relations. I'm saying it ought to be looked at. There is no one looking at this relation between UFO's and outages.

A Fall of Moondust?

So … EMP from Soviet Orbital Bombs or EMP from UFOs? It would seem that the jittery American psyche in 1965 was under a great deal of pressure from implacable, ill-defined forces from outer space. And if these concepts were two sides of some kind of cosmic coin, fate was about to provide another chance to call the toss.

On December 9, a month to the day after the Blackout, a strange object appeared to streak from the sky and impact near the small town of Kecksburg, Pennsylvania. According to researcher Robert Todd, OEP officer Col Bourassa was once again on the case, having received reports from widely separated witnesses concerning the meteor-like phenomenon. And an urgent military recovery effort is alleged to have occurred.

Notes and Sources

[1] Asif Siddiqi FOBS webpage: http://home.earthlink.net/~cliched/spacecraft/fobs.html

[2] The convoluted nature of this story is emphasized by the fact that the missiles displayed in the 7 Nov 65 parade were not the SS-9 Scarp FOBS, nor were they the SS-6 that had launched Vostok and Voskhod as Tass claimed. According to Russian Strategic Nuclear Forces, Pavel Podvig, ed, the displayed vehicles were actually the Korolev GR-1 "Global Rocket" (SS-X-10 Scrag) and mockups of the earlier R-26 missile which had been cancelled in 1962. Schlafly and Ward used a painting of the GR-1 on the cover of later editions of Strike From Space.

[3] Report to the President by the Federal Power Commission on the Power Failure in the Northeastern United States and the Province of Ontario on November 9-10, 1965.

[4] "[I]t was not learned until several days after the power failure that the two reds (nuclear detonation reports) were false indications caused by a peculiarity in the circuitry of the particular Bomb Alarm Console." Fritz, C. E., "Some Problems of Warning and Communication Revealed by the Northeast U.S. Power Failure of 9-10 November 1965," Institute for Defense Analysis Report R-142, April 1968, cited in Scott D. Sagan, The Limits of Safety: Organizations, Accidents and Nuclear Weapons. (1993: Princeton, NJ, Princeton University Press)

[5] See for

example the oral history interview at the Blackout History Project website:

http://www.blackout.gmu.edu/forum/interviews/eyewitness3.html;

also

http://www.niagarafallsreporter.com/ufo.html

http://www.virtuallystrange.net/ufo/mufonontario/archive/blkout.htm